Image: John Peet, Mount Cashel (detail), 2018, mixed media. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Curated by Wendy Peart, Curator of Education & Community Outreach

John Peet’s installation is the result of finding a box of old family photographs, including images of his grandfather’s time at the Mount Cashel Orphanage in St. John’s, Newfoundland in the early 1900’s. This institution was operated by the Irish Christian Brothers, a Roman Catholic lay order from 1898 -1990, and has been notably reported as a place where countless youth suffered abuses by those who were entrusted with their care and education. Through this work, Peet develops a posthumous relationship with his grandfather that is deepened by exposing the complex powerful systems that have enabled such tragic conditions. Through his work, he also uncovers the vital interconnectedness of the boys at the school who developed life-affirming friendships and familial bonds.

John Peet was born in St. John’s NL and raised in Montreal, QC. After moving to Regina, SK, in 1977 he began working in ceramics, exhibiting and marketing his work. He received his BFA from the University of Regina in 1994 and worked at the MacKenzie Art Gallery.

Essay ↑

Potting the Photograph

By Julia Krueger

“Imagine a world without things. It would be not so much an empty world as a blurry, frictionless one… there [wouldn’t] be anything to describe, or to explain, remark on, interpret, or complain about—just a kind of porridgy oneness. Without things, we would stop talking.”[1]

– Lorraine Daston

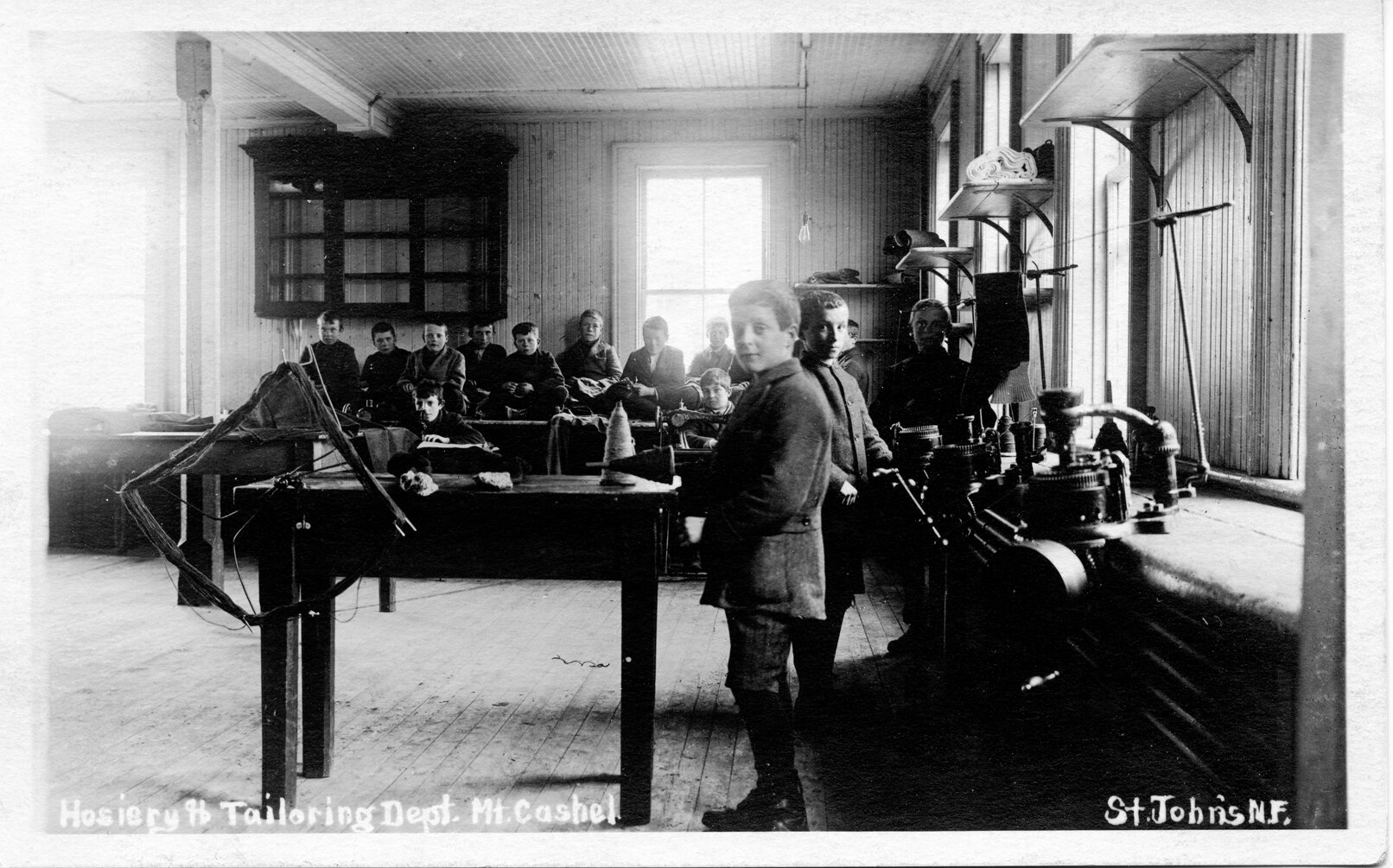

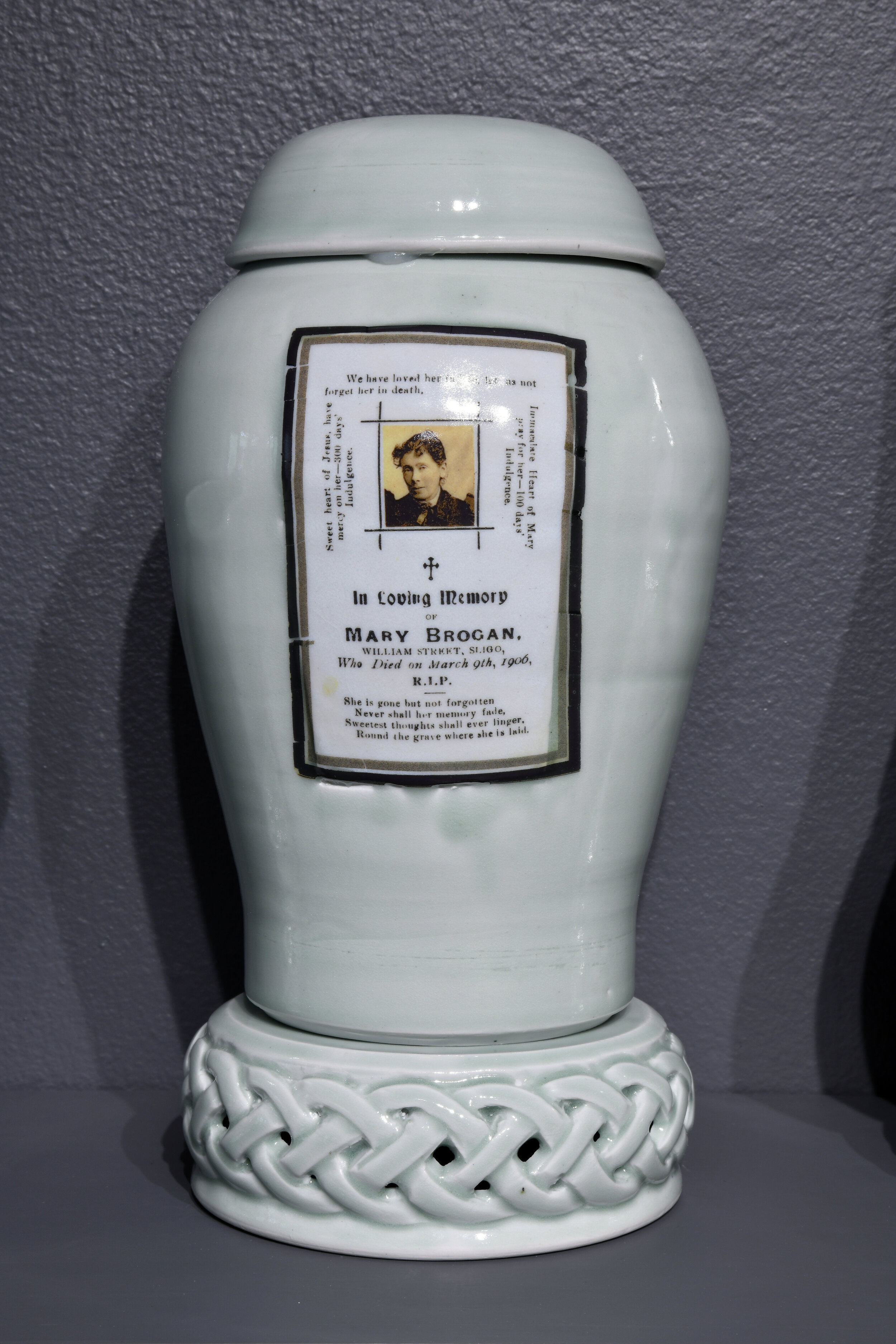

Patrick Brogan (fig. 1) was just a small boy when his parents died in 1906 and 1907 orphaning nine children. His oldest sister could manage the care of one but not seven others, and consequently they were split up and housed in different Irish institutions. It must have been so scary, isolating and life-altering. Young Patrick found himself in an orphanage run by the Irish Christian Brothers, a Roman Catholic lay order, and in 1912, he accompanied one of the Brothers to the Mount Cashel Boys’ Home in St. John’s, NL. There, Patrick was trained as a tailor, but he kept in touch with his family back in Ireland, exchanging photographs and letters throughout his life. Eventually, he married a local Newfoundland woman and had two children—a boy and a girl. However, tragedy struck the family again when Patrick Brogan died of a stroke at the age of 48. His grandson, Regina potter John Peet, never knew him as his mother was only 11 when her father, Brogan, died. Peet only knows his grandfather through stories, letters and photographs, some he unearthed when sorting through old boxes.

How does a potter deal with a collection of old photographs? This was the question Peet asked himself when he started a series examining his family history through his grandfather’s photographs.[2] Peet was born in St. John’s, came to Regina, SK in 1977 and started working in clay in 1978 while studying ceramics at the University of Regina.[3] Of his 1993 two-person exhibition, Eileen Egerton Lampard notes: “Peet is more concerned with the symbolic use of images, colour, and form to convey a type of diagrammatic narrative for public viewing.”[4] This concern continues in his work today including in John Peet: My Grandfather’s Pictures at Dunlop Art Gallery, Sherwood Village Branch. The exhibition consists of two works—Leaving Ireland and Mount Cashel—which reactivate old family photographs through ceramic-driven installations rooted in active domestic display.

Leaving Ireland, 2021 is a garniture of seven decaled vessels arranged upon a mantel. The central jar has three images of Brogan fired onto its surface, and it is flanked by bottle forms covered in decals of other Brogan family photographs. These three along with the two end vessels also have decals of postcards and messages sent from family to Brogan when he was in Newfoundland. The two ginger jars are decaled with the funeral cards for Brogan’s parents—Peet’s great grandparents. A garniture is a specific ceramic form of installation tracing back to the 17th and 18th centuries when porcelain objects inspired by or from China, Korea and Japan were collected by the European upper classes. Rooms filled with porcelain collections, known as “China cabinets,” were created, and garnitures or groups of three, five, or seven porcelain vessels made specifically for arrangement and display were symmetrically arranged along brackets, shelves or overmantels and in and on top of cabinets (fig. 2).[5] Garnitures were symbols of wealth and indicated the owner’s access to a global trade network.[6] As garnitures became more affordable to the middle classes, in part thanks to Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795), they functioned as a way to update one’s decor and to fill the domestic interior with sweet smells.[7]

Mount Cashel, 2021 is a powerful ceramic installation of three six-foot wooden tables, six benches and 18 decaled porcelain place settings inspired by a photograph of Mount Cashel residents sitting at a table (fig. 3). Each hand-thrown porcelain modern setting (as opposed to 19th century seven-piece settings[8]) consists of three pieces: a plate, bowl and beaker decorated with decals and a carved band of Celtic knots which reflects Peet’s Irish heritage. The decals for each setting are cropped from one photograph from Brogan’s collection of Mount Cashel images taken during his time as a resident. For example, there is a photograph of the hosiery and tailoring department, and Peet has created a corresponding place setting (figs. 4 & 5). In terms of the history of photography, some of the earliest photographs of working-class children were taken following the implementation of Education Acts and the formation of groups such as the Church Lads’ Brigade (the Newfoundland chapter was established in 1892),[9] which were launched in part to reform young people and get them off the streets.[10] These photographs present disciplined and ordered views of children. Brogan’s Mount Cashel collection presents the Home as a place where young boys were provided with various social and educational activities that would form them into productive members of society—these are not images of children at play.

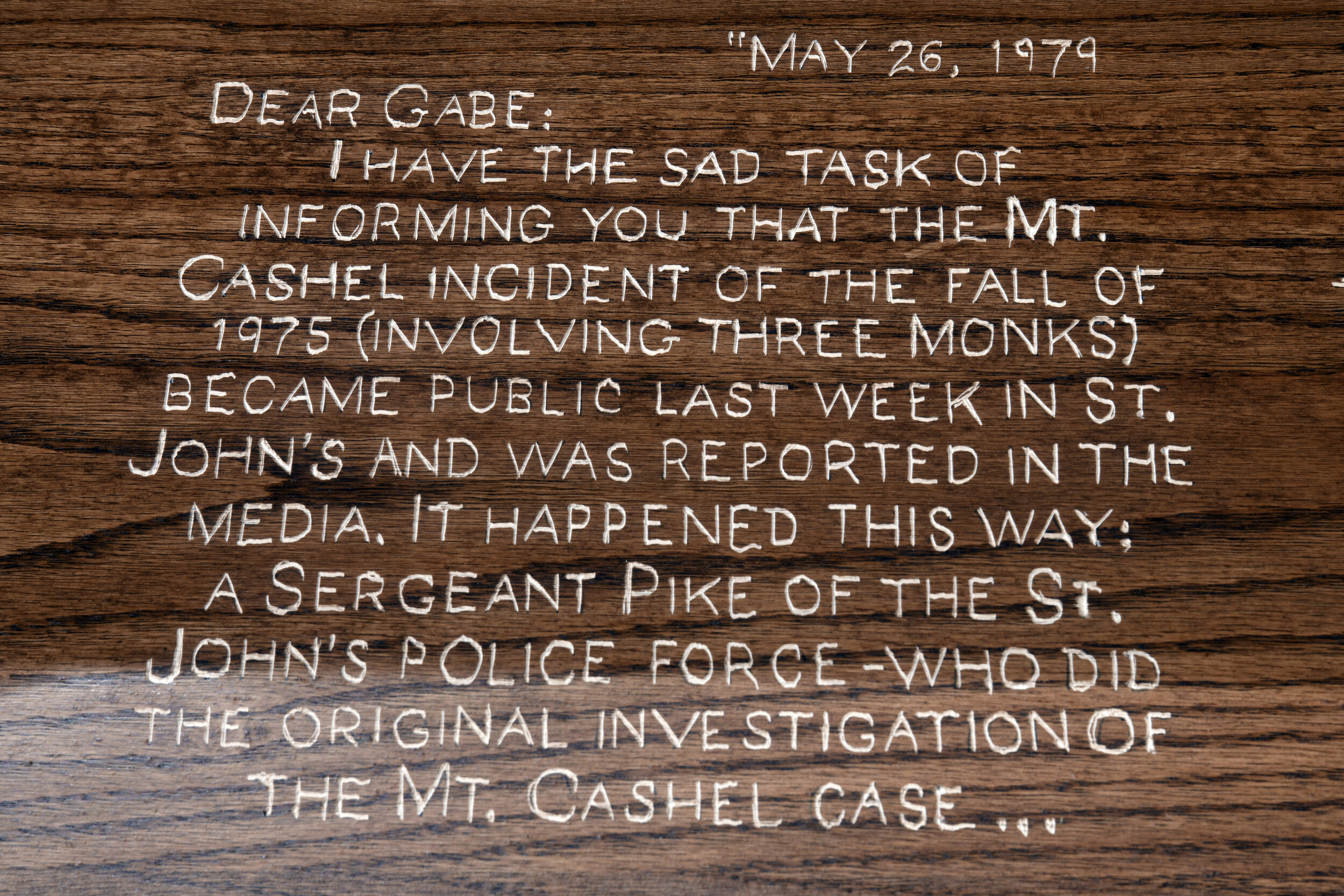

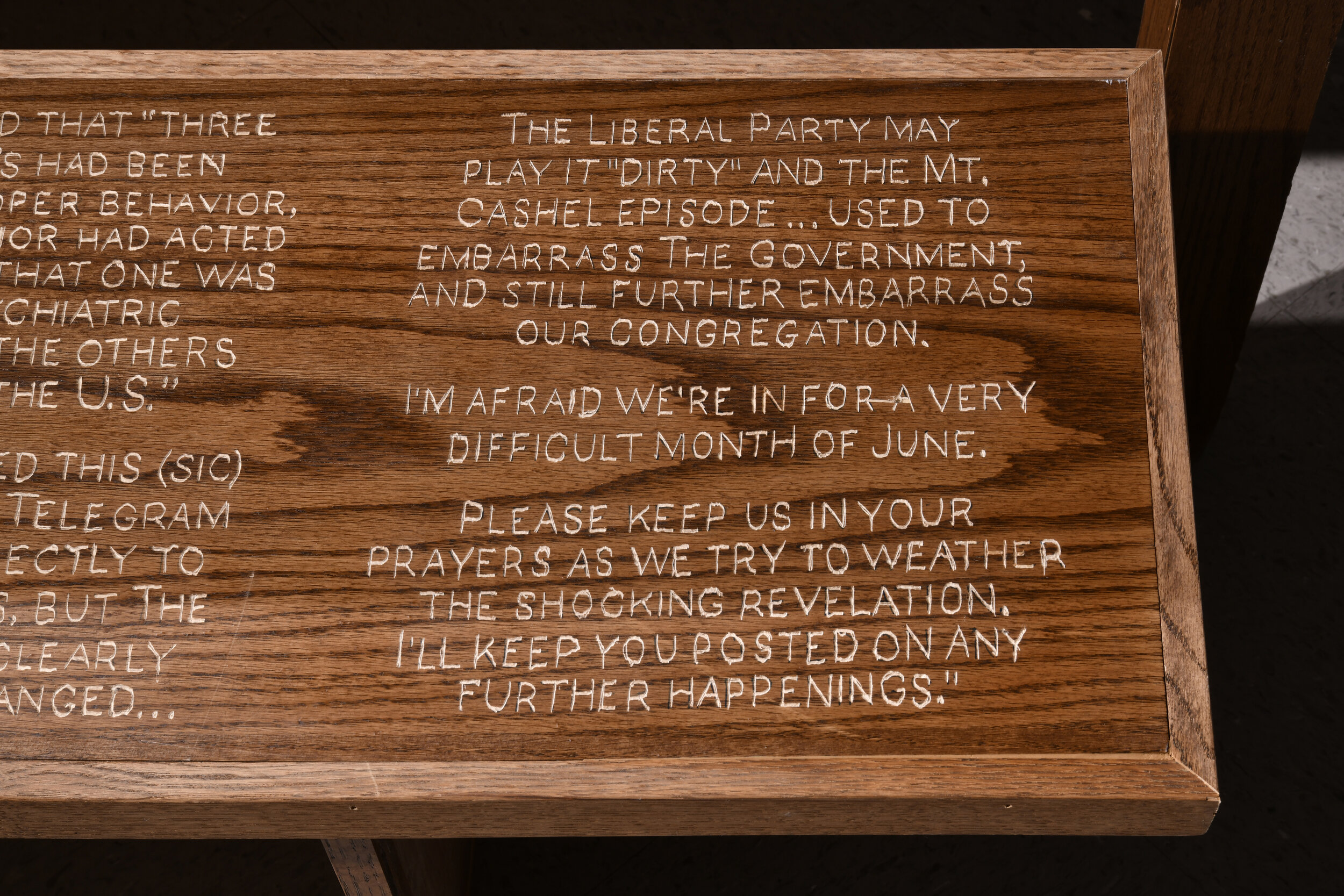

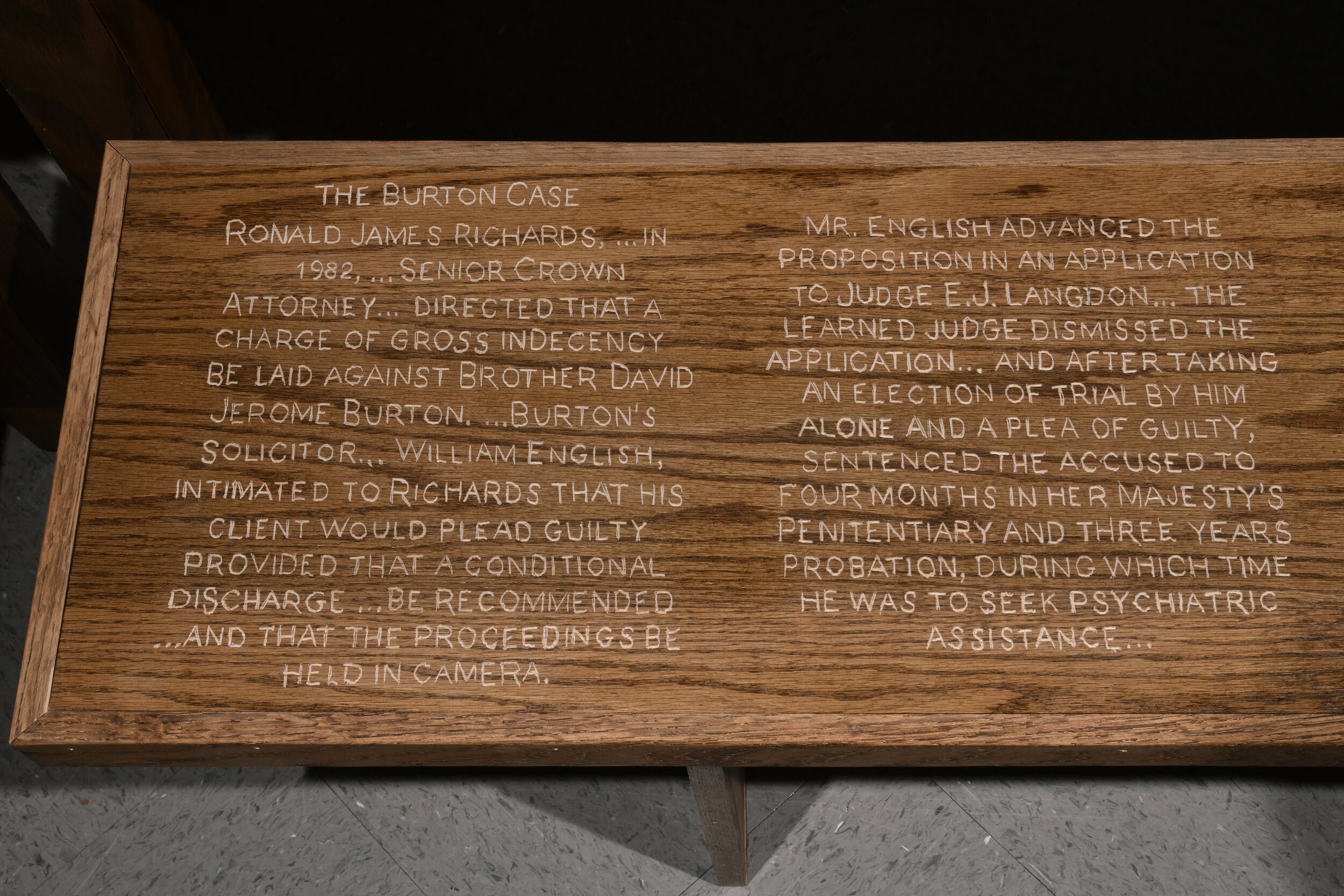

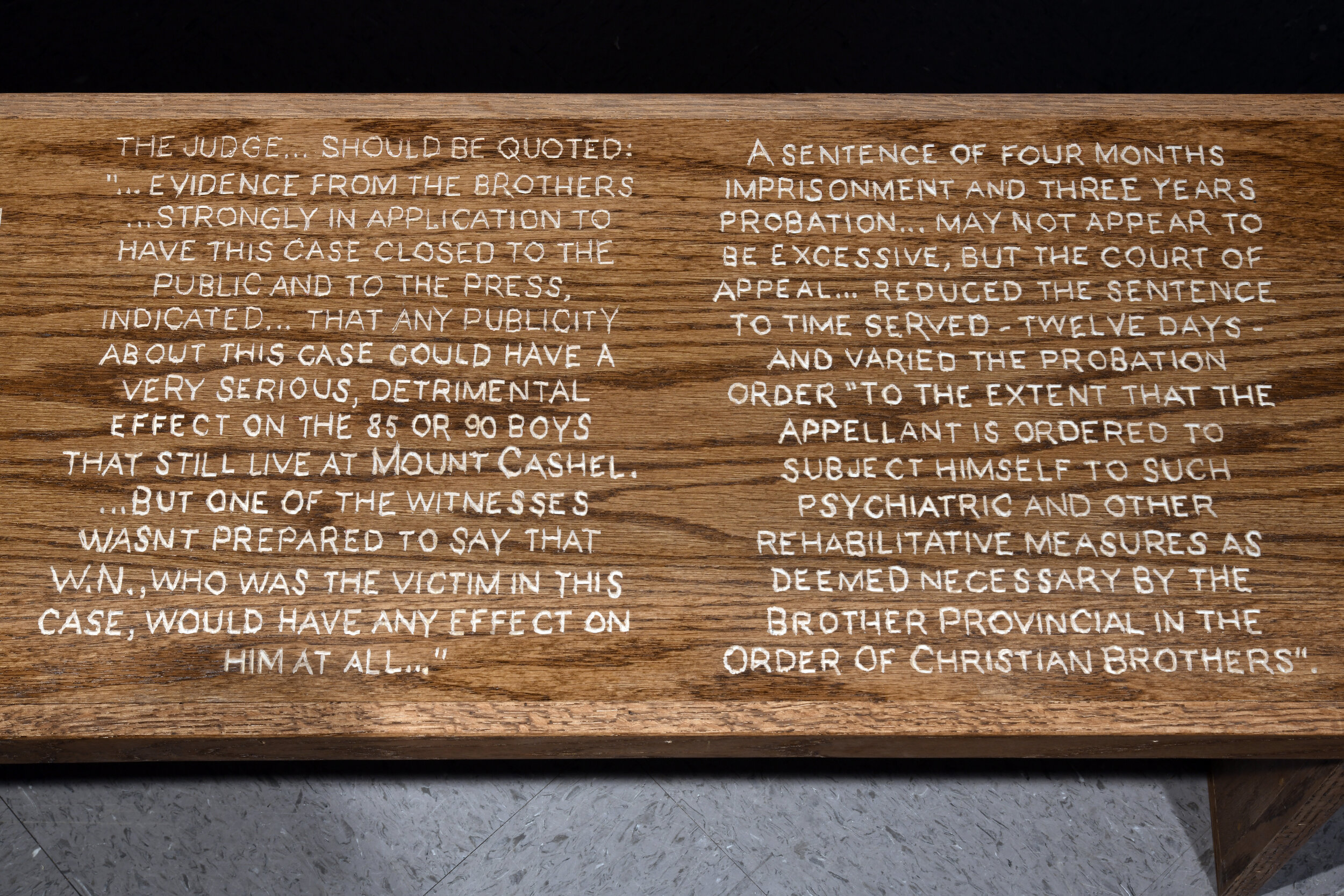

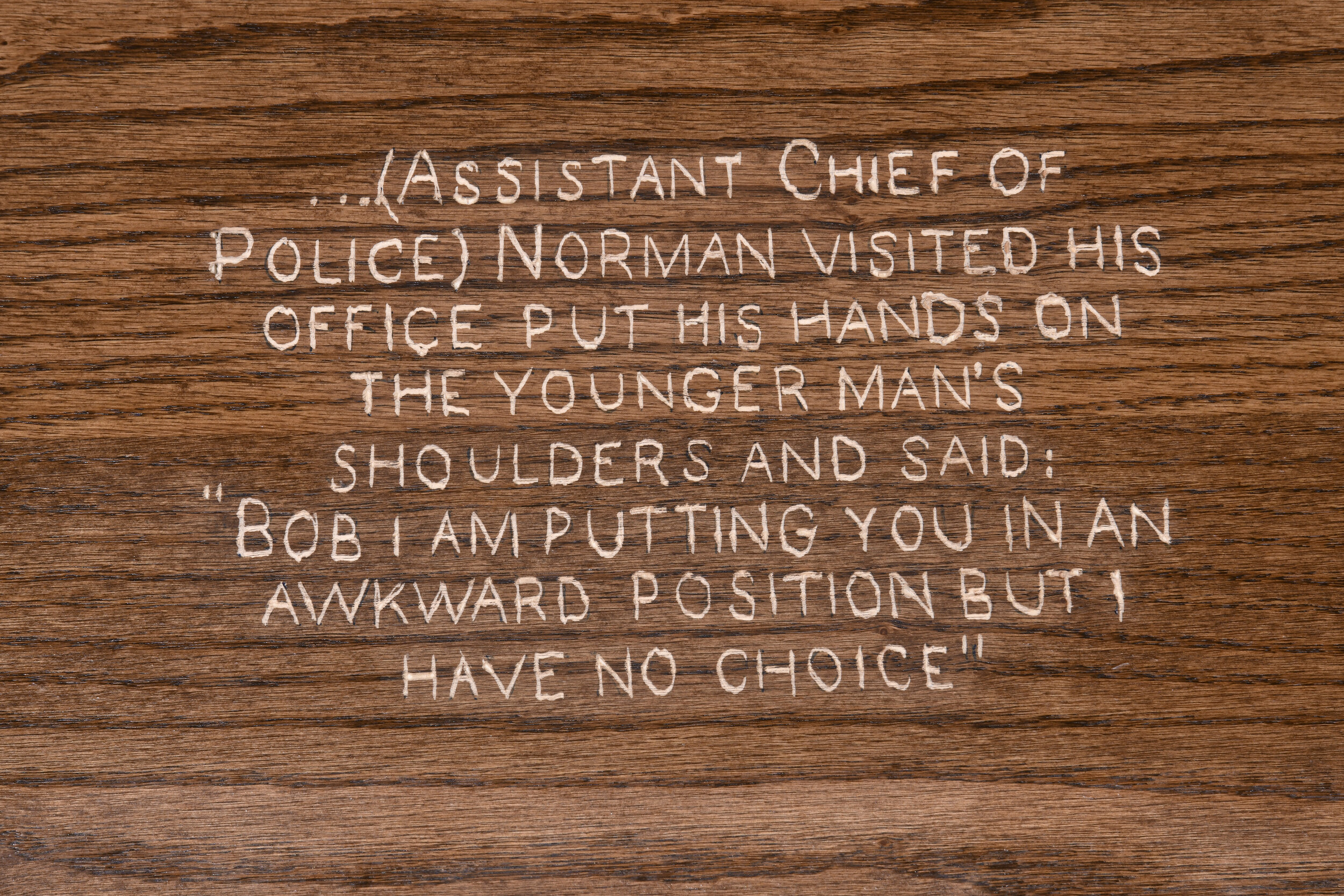

The Mount Cashel Boys’ Home was operated by the Irish Christian Brothers from 1898 to 1990. Beginning in the mid-1970s, reports “of repeated acts of physical and sexual abuse performed by Christian Brothers against boys who lived there as wards of the state” surfaced but were covered up.[11] In 1989, an inquiry chaired by Judge Samuel Hughes was established to investigate how the justice system had handled the reports regarding Mount Cashel and found a “stunning, collective failure of the judicial, police, religious, media and social service establishments to protect the interests of hopelessly vulnerable and cruelly abused children.”[12] In 1991, 87 charges were laid, nine Christian Brothers were convicted, and six years later, 40 victims were awarded compensation from the province. Each of Peet’s bench seats was carefully hand-carved by Peet with excerpts from the Hughes Inquiry transcripts highlighting the failures of those in power to protect those in their care.

Peet states, “Never having worked with photographic images in my art, I needed to find a way to use the photos that would speak to the issues I wish to address as well as work in the context of the object I create.”[13] So, returning to the question, how does a potter deal with a collection of old photographs? Peet deals with a collection of old photographs by engaging with image, context and object, by “potting the photographs” through a combination of surface decorating, reframing and referencing ceramics’ rich history of active domestic display strategies which focus an otherwise “porridgy oneness” into something that haptically and emotively talks. Ceramist Paul Mathieu explains that images on objects operate differently than when they are framed on the wall, printed in a newspaper or mounted in a photograph album because the object acts as a frame and objects, especially domestic ones, are multidirectional and can go anywhere.[14] This is especially true with domestic forms of ceramic display such as garnitures and table place settings as these objects are meant to move around within the home and to interact with one another. In the case of Leaving Ireland, family members whom Peet had never met are framed within a domestic context, and the garniture also references global trade and travel which is parallel to Brogan’s travel and distancing from his family. The pots are meant to be arranged so that they speak to one another—a potter’s reinterpretation of the careful placement of photographs within a photo album[15] or to the act of communicating with distanced loved ones. The Mount Cashel installation uses handmade pots, tables and benches as frames. Peet recalls:

“As a gay man I have had a difficult personal struggle reconciling my strong Catholic up bringing with my sexual orientation. This came to a head in the 1980s when I was involved with establishing Aids Regina, providing support for people with Aids and promoting public awareness of Aids and its transmission. At this time many within the church establishment were pushing back against the work we were doing. When the scandal surrounding Mount Cashel erupted in the late 1980s I faced a personal crisis due to my strong family connection with the institution. When viewing the images from my grandfather I revisited my emotions from over twenty years prior and as a visual artist I wanted to incorporate them in an art work.[16]”

Well-ordered children—the public positive persona of the Home and Peet’s family’s own romanticized memories of it—are framed by his pottery and the table. In turn, the table is framed by the benches which are hand-carved with the descriptions of the failures of those in power to protect the children in their care. To take a seat at this table, will physically impress upon the diner to consider their position—you will feel Hughes’ words as you look at the boys. Keep in mind science historian Lorraine Daston’s point: “Thinking with things is very different from thinking with words.”[17] And this is the power of craft and ceramics which Peet has so evocatively harnessed.

Peet recalls, “While in palliative care [a friend] was asked where she felt she would go when she died. She responded that she would be here in the memories of those who knew and loved her, then she would slowly move to the world of myth as stories were told about her, finally she would fade.”[18] The exhibition John Peet: My Grandfather’s Pictures brings Peet’s grandfather, Patrick Brogan, back into focus, back from the fade by potting the photographs he left behind. His story of coming to Canada is retold in a haptic, craft and ceramic-centered way, leading to new myths, stories and relationships between past, present and future. It has also provided Peet an opportunity to engage with his past and navigate his own present feelings surrounding difficult subject matter such as the discriminatory practices and failure of religious institutions.

[1] Lorraine Daston, “Speechless,” in Things that Talk: Object Lessons from Art and Science, ed. Lorraine Daston (New York: Zone Books, 2008), 9.

[2] The series consists of: Forgotten, 2018; Mount Cashel, 2021; Leaving Ireland, 2021; In the Company of Friends, 2021 and one work yet to be made. Telephone conversation with the author, March 14, 2021.

[3] Over the course of his ceramics career, Peet was owner and operator of Echo Lake Pottery, Fort Qu’Appelle, SK (1983–1985); was a CUSO Volunteer Project Coordinator and Pottery Instructor at Sotuma Sere Pottery, The Gambia, West Africa (1988–1990); Visiting Pottery Instructor at Devon House Clay Studio, St. John’s, NL (1996); and taught pottery with the City of Regina (1990–2000). In addition, he has exhibited solo and group shows in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland.

[4] Eileen Egerton Lampard, Waterways: John Peet/James Slingerland (Regina: Rosemont Art Gallery Society Inc., 1993), np.

[5] J. Paul Getty Museum, “Garniture of Three Lidded Vases and Two Open Vases,” http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/5508/unknown-maker-garniture-of-three-lidded-vases-and-two-open-vases-chinese-kangxi-reign-about-1662-1722/ (accessed April 12, 2021).

[6] Patricia Ferguson, “Vase madness: the craze for garnitures,” http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/article/garnitures (accessed April 12, 2021).

[7] Different covers or lids were designed to shift the use of the vessel from a potpourri holder, to a flower vase and to a bud vase.

[8] Sandra Alfoldy, “The Function of Ceramics,” in On the Table: 100 Years of Functional Ceramics in Canada, eds. Sandra Alfoldy and Rachel Gotlieb (Toronto: Gardiner Museum, 2007), 115.

[9] “The C.L.B. (Church Lads’ Brigade) in Newfoundland and Labrador,” https://theclb.ca/about-the-c-l-b/ (accessed April 12, 2021).

[10] Patricia Holland, “‘Sweet it is to scan…’ Personal photographs and popular photography,” in Photography: A Critical Introduction, 2nd edition, ed. Liz Wells (London: Routledge, 2000), 136.

[11] Jenny Higgins, “Mount Cashel Orphanage Abuse Scandal,” https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/politics/wells-government-mt-cashel.php (accessed April 12, 2021).

[12] Ibid.

[13] John Peet, 2021 artist statement.

[14] Paul Mathieu, “Object Theory,” in Utopic Impulses: Contemporary Ceramics Practice, eds. Ruth Chambers, Amy Gogarty and Mireille Perron (Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2007), 119.

[15] Holland states, that “Curator Pam Roberts of the Royal Photographic Society…makes the point that the way photographs have been selected and put together is an important part of the personal meaning of the pictures in an album.” Holland, “‘Sweet it is to scan…’,” 132.

[16] Peet, 2021 artist statement.

[17] Daston, “Speechless,” 20.

[18] Peet, 2021 artist statement.

Writer Biography

Julia Krueger was born and raised in Regina, Saskatchewan. She studied art history and Canadian art history at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario. She received her BA with highest honours and her Master’s thesis: “Prairie Pots and Beyond: An Examination of Saskatchewan Ceramics from the 1960s to Present” was accepted in 2006 with distinction. In 2010, Julia completed a BFA in ceramics at Alberta College of Art and Design in Calgary, Alberta, where she collaborated on many projects with her sister, Yolande Krueger.

Figure 2 Caption: Lambertus van Eenhoorn (1651–1721), De Metaale Pot Factory Garniture, ca. 1690, tin-glazed earthenware, Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Sid R. Bass Gift, in honor of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2006, 2006.309.1-5. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/232031

Installation Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall

Media ↑

My Grandfather's Pictures: artist John Peet reflects on the past CBC LISTEN Live Radio